GBS: what every pregnant woman should know about group B strep

This page contains affiliate links, which means we may earn a small amount of money if a reader clicks through and makes a purchase. All our articles and reviews are written independently by the Netmums editorial team.

Group B strep (GBS) is a common bacteria that many of us have in our body. During pregnancy, it can sometimes cause complications which can sadly be very serious. Read on to learn all you need to know about group B strep, including the risks, info on testing, and what it means for you and your baby.

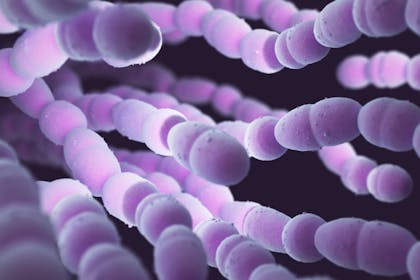

What is group B strep (GBS)?

GBS is a very common bacteria, which around 40% of adults carry (usually in the gut, bowel or vagina). The official name for the bacteria is group B streptococcus, or streptococcus agalactiae. Contrary to belief, GBS is NOT a sexually transmitted disease.

GBS usually does no harm and rarely causes any symptoms, so you won't feel unwell or even know you are GBS positive.

In most cases, pregnant women who have GBS don't experience any problems as a result. But if a women has GBS when she gives birth, it can sometimes pass to her baby. If not treated promptly, this can lead to health problems for the baby, which can sadly be very serious.

FREE NEWBORN NAPPIES

How often does GBS affect newborn babies?

About one in every 1,000 babies born in the UK develops group B strep infection. That's according to Group B Strep Support, the only UK charity dedicated to wiping out group B strep infections in babies.

On average in the UK:

- two babies a day develop a group B Strep infection

- one baby a week dies from their GBS infection

- one baby a week survives with long-term disabilities – physical, mental or both

How serious is GBS in babies?

Although a group B strep infection can make a baby very unwell, most babies make a full recovery with prompt treatment.

However, the infection can sometimes cause life-threatening complications, such as:

- blood poisoning (septicaemia)

- infection of the lung (pneumonia)

- infection of the lining of the brain (meningitis)

'GBS is the most common cause of severe infection in newborn babies, and the most common cause of meningitis in babies under three months of age,' says Jane Plumb, MBE, chief executive of the charity Group B Strep Support, whose son Theo died from a GBS infection in 1996.

However, the NHS stresses that most of the one in 1,000 babies who develop group B strep make a full recovery.

What are the signs of GBS in babies?

If GBS bacteria are passed to a baby during labour and birth, and the baby becomes infected, they'll usually develop symptoms within 12 hours of birth. This is known as early-onset GBS infection.

Symptoms include:

- being floppy and unresponsive

- not feeding well

- grunting

- high or low temperature

- fast or slow heart rates

- fast or slow breathing rates

- irritability

Late-onset GBS infection develops seven or more days after a baby is born. This usually means the baby probably became infected after the birth – for example, they may have caught the infection from someone else.

GBS infections after three months of age are extremely rare.

Typical signs of late-onset group B strep infection are similar to those associated with early onset infection and also include signs associated with meningitis, such as:

- being irritable with a high-pitched or whimpering cry, or moaning

- blank, staring or trance-like expression

- floppy, may dislike being handled, be fretful

- tense or bulging fontanelle (soft spot on babies’ heads)

- turns away from bright light

- involuntary stiff body or jerking movements

- pale, blotchy skin

If your baby shows signs consistent with GBS infection or meningitis, call 999 or go straight to your nearest paediatric A&E department.

If your baby has a GBS infection or meningitis, early diagnosis and treatment are vital: delay could be fatal.

How can GBS in babies be prevented?

If a woman has GBS, it's possible to prevent it from passing to the baby by giving her antibiotics during labour. However, this isn't recommended for all women with GBS for several reasons:

- Most women with GBS won't pass the infection on to their baby.

- Even when a baby does become infected, prompt treatment usually leads to a full recovery.

- Doctors try to avoid giving antibiotics unless it's really necessary. Overuse of antibiotics leads to antibiotic-resistant superbugs, and healthcare professionals are very concerned that if we keep using antibiotics too much, eventually they'll stop working. The World Health Organization lists overuse of antibiotics as one of the top 10 threats to global health.

This is why the NHS doesn't offer routine testing for GBS; even if you have it, taking antibiotics may do more harm than good. However, if you're worried about GBS, you can still get tested privately (see below).

The NHS recommends that you only take antibiotics for GBS if you're in a high-risk group. This includes:

- If you go into labour prematurely (before 37 weeks)

- You've previously had a baby with a GBS infection

- It's been more than 24 hours since your waters broke

- You have a high temperature during labour

In these cases, your baby is more likely to be infected, so you should be offered antibiotics during labour. You should also be offered antibiotics if a routine test or private test has shown that you have GBS.

Getting tested for GBS

I'm pregnant – how do I know if I'm GBS positive?

The NHS says that roughly one in five pregnant woman in the UK carries GBS in their digestive system or vagina.

But because of the symptom-less nature of carrying group B strep, most women will not know they are carriers. Having a test is the only way to establish whether you're a carrier or not.

However, in the UK, pregnant women are not routinely offered testing for group B Strep, unlike in many other developed countries. If your NHS trust doesn't offer it (and most don't) you can get a test done privately (see below) for less than £40.

Routine antenatal urine tests may detect group B strep, though usually only when you have a urinary tract infection caused by the bacteria.

Where can I have a GBS test done?

The only reliable home test to detect GBS carriage is called the Enriched Culture Method (ECM) test, which is available privately and from a small number of NHS trusts – so do check if yours offers it. The test involves taking vaginal and rectal swabs during the third trimester of your pregnancy.

It's important to do the test towards the end of the third trimester (between 35 and 37 weeks) to get the most accurate result. Don't leave it too late in case your baby arrives before you've had chance to do the test and get the results.

Private testing costs around £40. You can also find out more at the GBSS website, run by the charity Group B Strep Support.

GBSS recommends home testing kits from The Doctors Laboratory. You can find information on where to buy them here.

Other than this, the NHS may offer you a test if you're in a high-risk group (see above).

Results can be available in 30 minutes.

Can I self-test for GBS?

You can purchase a home-testing pack online, which costs about £40 for the test, processing the swabs and sending you (and your midwife if you select that option) the results.

Or you can call The Doctors Laboratory on 020 7307 7373 to order a group B strep test.

Worried about being GBS positive:

Help – I'm GBS positive and pregnant. What now?

If you're tested for GBS and the results are positive, make sure you tell your antenatal team. It should be recorded in your antenatal notes and even written in big letters on the front ready for your delivery midwife to see come due date.

As soon as you think you're in labour, call up your triage number or midwife and tell them that you're GBS positive. They will probably want you to come in sooner so that you can start antibiotics in plenty of time before the baby arrives.

I'm GBS positive – what are the chances of my baby getting it?

'If a mother is a GBS carrier, there's a 50% chance she'll pass the bacteria on to her baby during labour,' says Jane.

'And that baby has a one in 300 chance of developing a GBS infection if no preventative measures are taken.'

That means that, if you have GBS, there's about a one in 600 chance of your baby developing an infection.

How will I be treated for GBS during labour?

Antibiotics are given intravenously (through the vein) to stop mothers passing the infection on to their babies. These should be given immediately at the start of labour and then at intervals until delivery.

Ideally, antibiotics should be given for at least four hours before the baby is born. That's why it's important to contact the labour ward as soon as you're in labour and remind them you are GBS positive. Antibiotics are not useful until labour has started.

Once born, your baby will be monitored closely for symptoms of GBS. If your baby appears healthy, no antibiotics will be required.

Is it safe to take antibiotics for GBS during pregnancy?

With something as serious as group B strep infection, prevention is much better than treatment. Giving intravenous antibiotics in labour to women known to carry group B strep could reduce GBS infection in their newborn babies by more than 80%.

However, the use of any drug, including antibiotics, is not without risk. Some women will prefer not to have antibiotics if their risk is only slightly increased, since it may complicate an otherwise natural birth, and will also contribute to the issue of antibiotic resistance.

If you're allergic to penicillin, make sure you tell your midwife. Penicillin is the antibiotic routinely given to women in labour so it's important that those looking after you know this and that it's included in your medical notes. There are alternative antibiotics that can be given if needs be.

If I have a C-section, will that stop my baby getting GBS?

Planned caesareans are not recommended to mothers carrying GBS as a way of preventing infection being passed onto babies.

If you are a carrier and are having a C-section, you will not usually be given antibiotics if the surgery begins before your waters break. This is because the risk to the baby of infection if so low.

But if your waters do break and your labour begins before your C-section starts, you should be treated with antibiotics as per a vaginal delivery.

This is also the case for non-planned, emergency caesareans.

I was GBS positive with my first baby – will I need another test for my next?

If you've had a baby with GBS infection before and you're pregnant again there is no need for further testing – you should always be offered intravenous antibiotics from the start of labour in all subsequent pregnancies.

The Positive Birth Book: A New Approach to Pregnancy, Birth and the Early Weeks Paperback by Milli Hill is a must-read for expectant parents. See more details here at Amazon.

Find out more about GBS

Group B Strep Support (GBSS) is a UK charity providing clear, thorough information and advice on GBS. You can find out more about testing and read additional info about treatment in pregnancy and for newborns.

Do you think GBS screening should be rolled out across the UK? Have you paid for a private test in pregnancy?

Share your thoughts and opinions in the chat thread, below.