Giving birth: labour, delivery and the afterbirth

This page contains affiliate links, which means we may earn a small amount of money if a reader clicks through and makes a purchase. All our articles and reviews are written independently by the Netmums editorial team.

The most daunting thing about being pregnant is undoubtedly giving birth. Knowing what to expect and what really happens can hugely help with any anxiety. Will it be painful? How do you push? What's the afterbirth? Here's what you need to know.

How to give birth: what are your options?

There are two main options when it comes to giving birth:

- vaginal

- planned caesarean (elective caesarean)

Most antenatal appointments will gear you towards a vaginal birth, which is the most common option.

A planned or elective caesarean – also known as C-section – is usually recommended for medical reasons only. That's because it's a major operation and comes with risks as well as benefits.

FREE NEWBORN NAPPIES

However, it will be advised that you have your baby by C-section if:

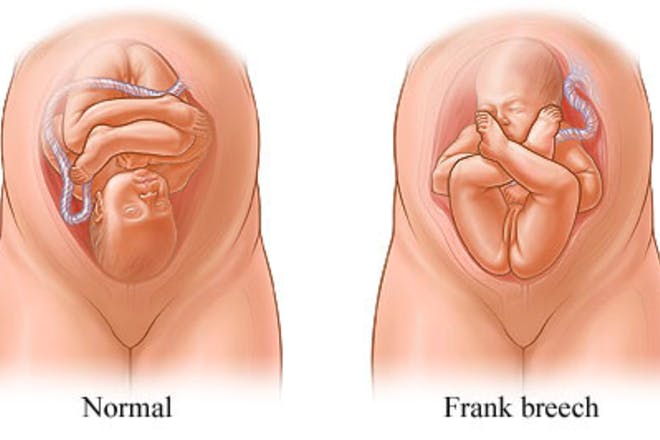

- your baby is in the breech position (upside down or back to back)

- you have a pregnancy condition like placenta praevia, pre-eclampsia or high blood pressure

- you have an infection such as HIV, that you don't want your baby to contract.

According to the Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists (RCOG), one in every five pregnant women in the UK will have a C-section. About half of these are as a planned operation and the other half are as an emergency.

If you wish to have a C-section for non-medical reasons, you can still make this request to your midwife, as you're entitled to have a C-section if you want to.

If you do have a C-section or have had a C-section previously, it's still possible to have a vaginal birth, provided it's considered safe for you to do so. Having a vaginal birth after C-section is called a VBAC.

Where can you give birth?

As well as choosing how to give birth, you can decide where to give birth, either:

- at hospital

- in a birth centre

- at home

Your midwife will discuss your options at your antenatal appointments, but provided you have a healthy and low-risk pregnancy, you should be able to choose the one that most appeals or suits your needs.

Despite the different options on offer, most mums these days still choose to give birth in a hospital. The advantage of this is that even though you'll be looked after by midwives, you'll have a team of medical experts close by. Many mums find this reassuring, just in case anything goes wrong.

Another option is to book into a birth centre or midwife-led unit for your labour. These units usually offer a modern and homely environment, such as private rooms with birthing pools and en-suite bathrooms, TVs and often facilities for dads to stay overnight, too.

However, as birth centres are run exclusively by midwives, you won't be able to have an epidural as this can only be administered by an anaesthetist in a hospital.

If having a baby at home appeals, discuss the logistics with your midwife. The advantages of a home birth can include:

- being in familiar surroundings

- not having to travel to hospital

- less likelihood of needing intervention, such as forceps or ventouse (source: NHS)

But remember that you may still have to be transferred to hospital during or after the labour if:

- the baby is in distress

- the labour is progressing particularly slowly

- you wish to have an epidural

- you tear or bleed badly during or after birth.

Currently, the NHS says that only 2% of mums have a home birth (in England), compared to around 94% who choose a hospital birth.

Pain relief: what are the choices?

If you're having a vaginal birth at hospital, you'll have a wide range of pain relief options to try, including:

- Paracetamol (recommended in early stages for mild contractions)

- Self-help (breathing, movement, water, massage, relaxation)

- Alternative methods (hypnobirthing)

- TENS machine

- Water

- Entonox (gas and air)

- Pethidine (or diamorphine)

- Epidural (ask if your hospital has a mobile epidural as opposed to a static one, to enable you to still move around during labour).

If you give birth in a birthing centre or at home, you won't have access to an epidural as pain relief but you should still be able to request gas and air or pethidine.

Find out more about each one here.

How to help yourself during labour

While pain relief is one way of coping with giving birth, there are other ways of helping labour go as smoothly (and as speedily) as possible. Here are some suggestions:

- Have your birth plan ready – and make sure your midwife knows about it. That way she can follow your wishes or help you follow it.

- Choose your birth partner – remember, this doesn't just have to be your partner. Some women book to have a doula (a birthing support) to help you stay calm, informed and focused during labour.

- Keep on moving – although you'll have a bed in your hospital room or birth centre, don't feel like you have to lie in it. Bouncing or sitting on a birthing ball or going on all fours can be a great way to get the baby into a better position, which can also help relieve pain and make labour go more smoothly.

- Try different positions – walking around, leaning against a wall or hugging a birthing ball can all help you work through contractions and keep labour progressing.

When things don't go to plan: complications in labour

Everyone hopes for a smooth labour but it's a good idea to be prepared for some of the complications that can happen in the run-up to the birth.

These could include:

- Induction

- Interventions (assisted delivery)

Read more about being induced here.

Interventions or assisted deliveries occur in around one in every eight births, and are likely to involve:

- episiotomy – a precise cut in the perineum (the area between the vagina and anus) to help give your baby more room to get out and speed up delivery. Although it sounds unpleasant, you won't feel a thing if you've had an epidural. Your midwife will use a local anaesthetic, if you haven't had an epidural.

- ventouse – a bit like a suction cup, this grips on to the baby's head to help pull him out. Unfortunately, statistics say you'll be four times more likely to tear with ventouse, compared to with a natural birth.

- forceps – these smooth metal tongs are used to grip and pull the baby out of you. You may need an episiotomy or local anaesthetic beforehand and will be eight times more likely to tear with this method.

If the baby is in severe distress or in a breech position (upside down or back to back), you may be prepped for an emergency C-section to get your baby out as safely and quickly as possible.

What happens when it's time to push?

Stage one of labour, where contractions get regular and help your cervix open up ready to deliver the baby, can take hours or days. Find out more about the stages of labour here.

Once you're fully dilated (10cm) – the second stage of labour – it's time to actively start pushing to get your baby out into the big wide world. This part usually takes two or three hours at the most.

But how do you know how to push when you've never done it before?

Some midwives describe pushing as if you're trying to do a poo. This can help engage and relax the right muscles. And don't worry if you do a poo in the process – the midwives will quickly clean it up and will be used to it happening.

Some other tips for helping push your baby out include:

- taking short, sharp breaths with each contraction

- being upright so that gravity will help pull the baby down and out

- having a break if you need to restore some energy

- seeing or feeling where your baby is – midwives say this can help motivate mums that he's nearly here.

Just as you get into a rhythm with pushing, your midwife may tell you not to push. This is a good sign because it means the baby's head is ready to be born and she's trying to slow things down to avoid you tearing as it comes through.

To resist the urge, imagine you're blowing out a candle and make a 'hoo-hoo' sound to take short, sharp breaths.

And don't worry, you'll soon be meeting your baby!

How will your baby come out?

Most babies are born head first, curled up into a foetal position. A breech baby (feet or bottom first) will usually have been spotted in your final weeks of pregnancy and you'll be advised to give birth by C-section, if that's the case.

In rare cases, your baby can be head down in labour but then tilt his chin up rather than under. This is called face or brow presentation and can make it harder to push him out. If this happens, you'll most likely require intervention such as a ventouse, episiotomy – or an emergency C-section.

Watch the moment babies are born in the photo gallery below. (Avoid if you're squeamish though!)

Even once your baby is out, complications can still occur. Although they're rare in the scale of babies being born every minute, it's worth knowing about what can happen. For instance:

- the cord can get wrapped around your baby's neck

- your baby may not be breathing

- you may bleed too much

- you suffer a severe tear

- your placenta gets stuck.

What happens straight after you've given birth?

Once the baby's out, your emotions will be on overdrive. Knowing in advance what to expect can be a huge help in making things go as smoothly as possible.

Also known as the afterbirth, this is stage three of labour and includes getting rid of the placenta. You'll also have some decisions to make from your very first moments as a mum.

Here are some of the key things to happen after you've had your baby:

- Cord clamping (the umbilical cord – that brought nutrients and blood to the baby from the placenta during pregnancy – is cut to separate you and your baby)

- Skin-to-skin contact (your baby is put on your chest to start bonding and stimulate milk production)

- Delivering the placenta (your body has to get rid of the placenta – the organ that provides oxygen and nutrients to your growing baby during pregnancy – once the baby is out)

- Weighing the baby

- APGAR score (regular assessments of your newborn's health in the first minutes of being born)

- Stitches

- Vitamin K (an injection or oral dose to give your baby protection from bleeding and help his blood clot)

Some of the choices you'll face include:

- Do you want delayed cord clamping? Guidelines now advise waiting 1-5 minutes to allow newborns to benefit from iron-rich blood that continues to come out of the cord post birth.

- Who cuts the cord?

- Do you want to deliver the placenta naturally or with an oxytocin injection to speed it up.

- Do you want your baby to have a vitamin K injection?

Read more about the afterbirth choices you face here.

Your midwife will also be busy performing checks on you and your baby, and filling in paperwork.

Find out more about what your midwife does after birth here.

What happens next?

Once you've started to get used to the idea of being a mummy, you'll be brought the world's best tasting tea and toast. Then, as most wards are notoriously busy, you'll be moved to the postnatal ward.

Make sure you ask for a jug of water and something to eat – some wards take meal orders at specific times and you don't want to miss out.

On the postnatal ward you'll have regular visits from midwives and nurses who will check:

- your stitches and providing painkillers if necessary

- your pulse, temperature and blood pressure

- your catheter (if you had an epidural) and removing it

- you've done a wee

- your uterus is starting to shrink back to its original size

- feeding is going ok – ask for help if you're having latching on problems.

Your baby will have regular temperature checks, a hearing test and full newborn examination. If the ward is particularly busy, you may end up being discharged and then having to return a day or two later to have your baby's newborn check as an outpatient.

If you've had a normal, uncomplicated vaginal birth, you may be able to go home the same day. If you've had a C-section, you could be kept in as long as 3–4 days although sometimes less. Remember, it takes a good six weeks to recover from your operation.

Recovery from vaginal birth tears and episiotomy can also take several weeks so take it easy.

In the meantime, enjoy every second with your bundle of joy.