Epidural: what is it and should I have one?

This page contains affiliate links, which means we may earn a small amount of money if a reader clicks through and makes a purchase. All our articles and reviews are written independently by the Netmums editorial team.

If you're pregnant, you've probably heard of an epidural – a type of pain relief that's often used during labour. If you're not sure whether to have an epidural when you give birth, here's a detailed look at how it works, as well as the pros and cons of having one.

What is an epidural?

An epidural is a strong pain relief injection given in your lower back during labour. In most cases, it makes you completely numb from the waist down, so you won't feel any pain at all while giving birth.

According to patient.info, an epidural provides complete pain relief in about 95% of cases.

It's the most effective form of pain relief available for labour, but it's worth being aware of the pros and cons before deciding if it's for you.

FREE NEWBORN NAPPIES

How common are epidurals?

About 30% of births in the UK involve an epidural.

It's more common in women who have their labour induced: almost 50% of induced labours involve an epidural, compared to about 20% of labours that start naturally.

What are the different types?

Some hospitals may offer a mobile epidural (although not many). The advantage of this is that you retain some feeling in legs and feet.

This means you you can still move around and have an active birth to get the baby out as smoothly and quickly as possible. However, it does mean having a lower dose of pain relief, and you'll still need to have your baby's heart rate monitored.

Static epidurals are more common because they offer complete pain relief. The downside is that they will require you to be bed-based during labour because they'll numb your feet and legs as part of the pain relief process.

Some hospitals offer self-administered epidurals, which means that, once it's all set up, you can top up the dose yourself if you need to, rather than waiting for the midwife.

Can anyone have an epidural?

Most women can have an epidural if they choose to. Although it's sometimes not recommended if you have a health condition, such as an infection or a blood clotting disorder.

You should be able to discuss your pain relief options with your midwife during your routine antenatal appointments in pregnancy. On the day, your midwife and anaesthetist will double-check your health history and take into account any current medical conditions.

If you have a needle phobia, you may prefer a different form of pain relief.

If you want an epidural, you'll need to give birth in hospital; it's not available at birth centres (midwife-led units), or for home births.

How does an epidural work?

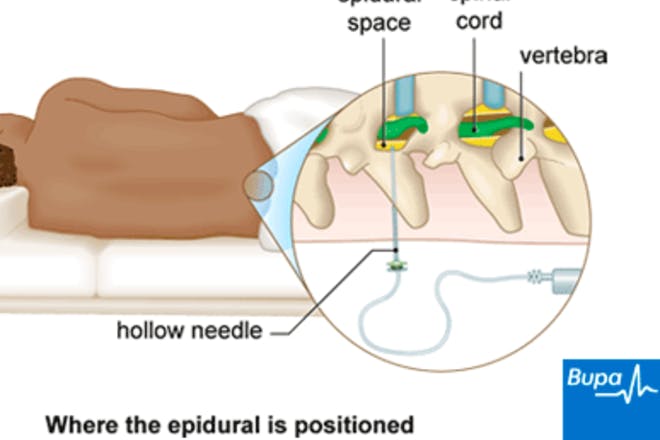

A local anaesthetic is injected into a space that surrounds your spinal cord, called the epidural space. This delivers the anaesthetic directly to your nerve endings, numbing pain quickly and effectively, without sending you to sleep.

When it's used during labour, it will mask the pain of your contractions without making you drowsy or sleepy, so you'll be fully aware of what's going on.

You'll have an injection into your lower back that leaves a small plastic tube (a catheter) attached. This is taped to you and connected via tubes to a supply of anaesthetic and pain relief drugs at the side of your bed. If and when it needs topping it up, this can be done instantly by your midwife.

What can I expect from an epidural?

Once you've been admitted to the labour ward and feel ready for an epidural, make sure you ask for it asap because it takes time to set up.

Your midwife will have to locate the anaesthetist on duty first of all, then it takes around 20 minutes to put it in, and another 20-30 minutes to start working.

The anaesthetist will explain the process to you, but here's what you can expect to happen:

- You'll dress in a sterile gown with a hole cut out in the back of it.

- Then you'll be asked to sit up on the bed and lean forwards, or you can lie on your side with your knees drawn up. This will help the anaesthetist to find the correct space in your spine to inject.

- The anaesthetist will clean the skin with a sterile solution and numb the area with a local anaesthetic, where the epidural is to be inserted.

- A needle is used to insert a fine plastic tube called an epidural catheter between the bones of your back.

- The needle is then removed, leaving just the catheter in your back ready to inject pain relief drugs into.

You'll also be given a drip (needle in your arm), which can be used to give you fluids to help maintain your blood pressure.

If the epidural starts to wear off or you need stronger pain relief as your labour progresses, your midwife can top it up.

Once you've had your baby and no longer need the epidural, it can take a couple of hours for any numbness to disappear.

You'll have to stay in your hospital bed until you get the feeling back in your legs and you'll need to wear support stockings (given to you by your midwife) to help with circulation.

Don't worry about needing the loo – you'll have a catheter to take care of that.

Will an epidural affect my baby?

There's no evidence that epidural pain relief causes any harm to your unborn baby during labour, nor does it have any long-term effect once the baby's born.

The only way an epidural could affect your baby, is if it causes your blood pressure to drop; this can affect the flow of oxygen and nutrients to your baby, which may require extra treatment or even a C-section.

That's why your baby's heart rate will be carefully monitored during your labour.

After they're born, all babies are given an Apgar score to show how healthy they are. Babies tend to have the same Apgar scores whether or not their mum had an epidural.

Are there any side-effects?

Epidurals are considered to be safe, but as with any medical procedure, there can be side-effects, such as:

- low blood pressure, which can make you feel dizzy or sick (this is rare though, as the fluids given via a drip will help to maintain your blood pressure)

- temporary loss of bladder control after the epidural (you'll be offered a catheter to help with this)

- itchy skin

- feeling sick

- headaches (caused by the bag of fluid that surrounds the spine being accidentally punctured – about one in 100 women experience this)

- temporary nerve damage (this is uncommon, and usually gets better within a few days or weeks)

- a local infection around the area of the injection (if this happens, antibiotics may be offered)

If you notice any side effects, mention these to your midwife as soon as possible so you can get appropriate pain relief or treatment.

Although having an epidural can cause short-term tenderness to your back for a few days after the birth, there is no evidence to indicate it causes long-term backache or permanent back problems.

Once the sensation returns, you may feel some tingling. If there's any pain, tell your midwife as she can give you some painkillers to help.

More serious complications, such as permanent nerve damage, are very rare.

If you're worried about the side-effects, talk it through with your midwife or anaesthetist.

Will an epidural mean I'm more likely to need a C-section?

No, research suggests that there's no evidence that you'll be more likely to end up giving birth via C-section just because you've had an epidural.

If you do end up having a C-section though, doctors will be able to top up your epidural to use as your anaesthetic, so there will be no hold-up to administer another one.

However, you may be more likely to need an assisted birth, where a doctor uses forceps (a bit like salad tongs) or ventouse (a suction cup) to help your baby be born.

You may also be slightly more likely to tear during labour or need stitches after giving birth. However, the risk isn't much higher than it is without an epidural.

Can I have an epidural at any stage of labour?

Early labour

Official guidance from The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) states that:

'You should be able to have an epidural at any point if you want one, including during the early stage of labour.'

In the past, healthcare professionals recommended against having an epidural too early, for fear of prolonging labour or increasing the chance of needing intervention.

However, more recent research has found that there are no more risks to having an early epidural than there are to having one later in your labour.

Late labour

You normally won't be able to have an epidural if your baby is already crowning, and some healthcare professionals may be reluctant to offer one once you're about 9cm or 10cm dilated. Because it takes time for an epidural to get set up, taking it too late in your labour won't help. It's also difficult to administer the epidural safely if you can't keep still in late labour.

Having an epidural: the pros

Considered the strongest form of pain relief, it's no wonder that an epidural is so appealing to mums-to-be. Here are some of the advantages of having one:

- It's a really effective form of pain relief – the majority of women who have an epidural don't need any other form of pain relief during labour.

- Once it's in, you or your midwife can top it up (without needing the anaesthetist) so you'll have constant pain relief throughout your labour.

- You won't be distracted by pain so you'll have more energy and will be able to focus fully on getting your baby out.

- You can still feel something – although epidurals block the pain of contractions, it is still possible to feel when they're happening and know when to push.

- It doesn't slow down the first stage of labour – despite often being 'blamed' for slowing down labour, NICE guidelines state that there's no proof of this in the first stage.

Having an epidural: the cons

As well as the side-effects mentioned above, disadvantages of having an epidural include:

- It takes time to work – as well as taking time to set up, it also takes a good 20 minutes to kick in. Not all hospitals have 24-hour access to epidurals either, or they could be particularly busy and need to wait until the anaesthetist is available.

- It isn't always 100% effective – the Obstetric Anaesthetists Association (OAA) estimates that one in 10 women who have an epidural during labour need to use other methods of pain relief.

- It may slow down the second stage of labour (pushing stage) in some cases – because you can't feel as much, you may find it difficult to push the baby out. If things don't progress or the baby gets into distress as a result, you may need to have an assisted delivery (using forceps or ventouse).

- You usually can't move around – as most epidurals numb your lower half of your body including your legs and feet, making it impossible to walk or move around. You'll also be advised to have continuous electronic foetal monitoring (CTG). This involves straps around your abdomen and being attached to an electronic machine, affecting your mobility during labour. So even with a mobile epidural, you won't be able to move far.

- You'll need a urinary catheter to help you wee – not particularly pleasant to have inserted or removed after labour.

- You'll be on a drip – in case your blood pressure drops, which could affect oxygen getting to the baby, you'll have a cannula in your hand or arm so that fluids and medication can be given quickly at any stage.

Epidurals: am I failure if I have one?

Choosing to give birth in a hospital labour ward with pain relief, such as an epidural, can make women feel like they've somehow failed and aren't brave or tough enough to give birth 'naturally'.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

However, this feeling of failure (linked to epidurals) is likely to have stemmed from a long-running campaign led by the Royal College of Midwives (RCM) to promote 'natural childbirth'.

The RCM had argued that more women should give birth naturally – without caesarean, induction, instruments or epidural. Some midwives may have tried steering mums-to-be towards using birth centres, where epidurals aren't an option and they can have a more 'natural' experience of childbirth.

However, in 2017, the Royal College of Midwives (RCM) announced plans to end this campaign, saying that women will no longer be told that they should have babies without medical intervention.

Backing this, Professor Cathy Warwick, chief executive at the RCM, believes no woman should feel a failure for choosing pain relief or other assistance with giving birth. She says:

'What we don’t want to do is in any way contribute to any sense that a woman has failed because she hasn’t had a normal birth. Unfortunately that seems to be how some women feel.'

The Positive Birth Book: A New Approach to Pregnancy, Birth and the Early Weeks Paperback by Milli Hill is a must-read for expectant parents. See more details here at Amazon.

Looking for more information on labour and birth? Check out our articles below, or swap tips with women who've been there in our forum: